Analysis of JNIM’s Devastating Attack on Bamako and Its Implications for the Future of Mali

September 2024

For over 10 years now, the Islamist extremist groups Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State Sahel (IS-Sahel) have each taken significant segments of Malian territory, much of it in the north and centre of the country. Yet aside from a major attack in 2015, Bamako has remained largely untouched by the bloodshed and conflict that have come to engulf swathes of Mali.

But over the past two and a half years, JNIM has been noted as moving closer to Bamako, indicating that the city’s relative safety from terrorist violence was unlikely to last forever. When the sound of gunshots and explosions began echoing through the city early Tuesday morning, it was apparent that terrorists had reached the capital once again.

How The Attack Unfolded

These sounds marked the beginning of an hours-long JNIM assault on the Malian capital — one of the al-Qaeda affiliate’s most audacious and successful attacks to date. Two locations were attacked almost simultaneously, with clashes first reported at a gendarmerie training school in Faladié, housing an elite special forces unit to which Colonel Goïta belongs. Fighting at the school, which lasted for over three hours, led to a majority of the purported 70 casualties.

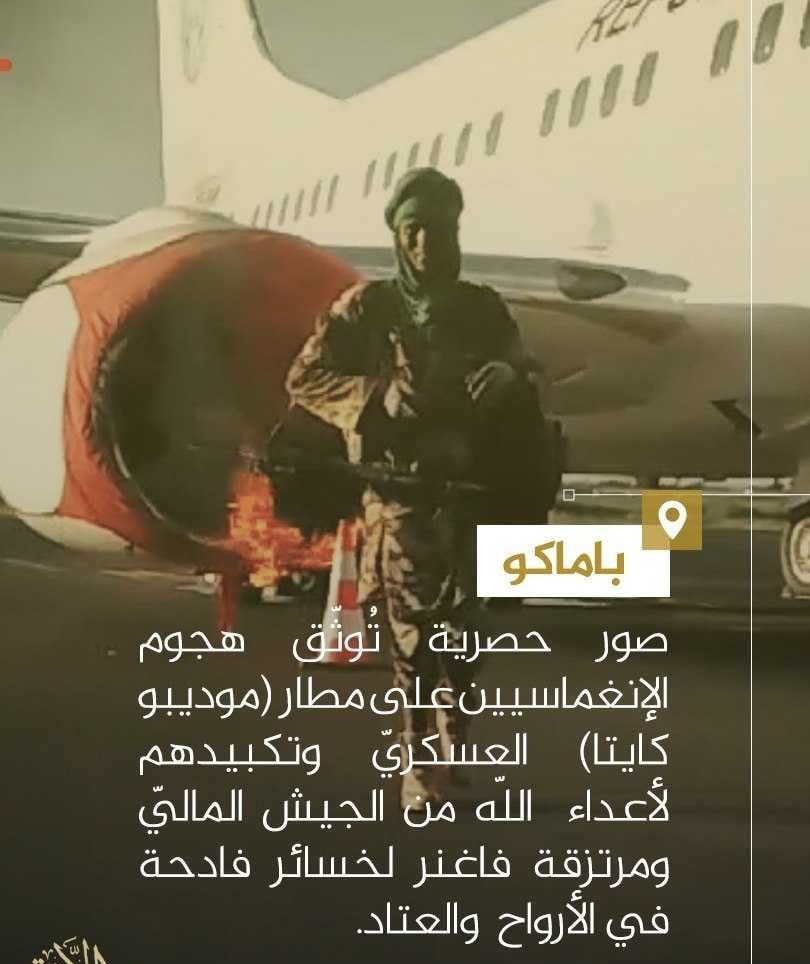

A second group of fighters attacked Air Base 101, a government and military facility located on the southern perimeter of the civilian Modibo Keita International Airport in Sénou. Fighting lasted far longer at this base, and while JNIM killed fewer security forces there, its fighters inflicted significant damage on buildings and planes located at the facility. Among the planes confirmed to have been affected was the government’s Boeing 737, reported to have recently been used by leader Assimi Goïta, in addition to an aircraft used by the World Food Program and one belonging to Sky Mali. The images and footage captured of JNIM fighters freely wandering beside airplanes, as well as inside one of the country’s most strategically important sites, have served as compelling propaganda for the group.

By nightfall, the military had repelled the attack and regained full control of Bamako. Malian authorities have not published information on how many were killed in the attack, admitting only that there had been “some” deaths; nor have they confirmed any of the speculated loss of aircraft. JNIM reported to have killed or wounded over 100 Malian and Russian security personnel, destroyed six military aircraft (including a drone), and disabled several others. The group’s statement also noted that many other vehicles and pieces of equipment were destroyed during the attack.

The junta is unlikely to do anything other than minimise the scale of the destruction and loss of life in the capital, while JNIM is known to inflate their claims, meaning the true extent of the damage — both in terms of personnel and equipment — is difficult to accurately ascertain. However, there are unique dimensions to this attack that are just as revealing as a casualty figure and necessitate further attention.

The Attack’s Unique Dimensions

The attack on two such symbolic military sites sent a message to president Goïta. The assault on the Malian leader’s former military base and images of a JNIM fighter setting fire to one of his personal planes underscores that the group has both the capability and desire to strike at Mali’s centre of power. Moreover, strictly attacking military targets, JNIM has again tried to differentiate itself from the junta, whom it frequently accuses of killing civilians.

And it is also telling that such a large-scale, coordinated attack was successful despite striking ‘harder’ military targets. JNIM’s success on Tuesday says much about the Malian security apparatus’ deficiencies, yet it equally reflects the group’s offensive capabilities, which have grown immeasurably over the past decade. JNIM’s evolution as a fighting force will continue further, much to the detriment of Sahelian governments and militaries.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of this story was revealed following the attack, when JNIM reported that the operation was conducted by two teams of “inghimasi” (suicide fighters) from the sub-group Katiba Macina. Salman al-Bambari, an ethnic Bambara, the main ethnic group of Bamako, headed the first unit that struck the gendarmerie school. Abdul Salam al-Fulani, an ethnic Fulani, one of the most prominent ethnic groups in West Africa, targeted the airport.

Fulani involvement in this attack would not alarm a Bamako resident or a government official; this ethnic group is often associated with jihadists across the region. Yet footage of al-Bambari’s pre-attack vows being recited in Bambara may have come as a surprise to some. This footage of the two commanders is an implicit decision by JNIM to underscore their trans-ethnic makeup, as well as demonstrate that their message can resonate with individuals from any background.

JNIM and The Goïta Administration — Two Contrasting Trajectories

The attack in Bamako is yet another recent high-profile victory JNIM has been able to claim in Mali, with the group participating in the humiliating defeat of Malian and Russian troops at Tinzaouaten toward the end of July. While JNIM continues to enjoy much success in Mali, the Goïta administration is currently experiencing its most testing period to date. And despite the multitude of threats facing the country, it is the junta’s inertia in recent months that has arguably contributed the most damage to its reign.

The fatal defeat at the hands of JNIM and The Permanent Strategic Framework for Peace, Security, and Development (CSP-PSD) at Tinzaouaten came as a result of the junta’s underestimation of the resources and manpower required to reestablish control over the area, alongside a desire to reconquer the north at the expense of other pressing needs. The defeat was a significant blow to the credibility of the junta, both domestically and internationally. Evidence suggests that Goïta has sent another column from Gao to Kidal, from where it is anticipated to eventually head northward toward Tinzaouaten; the attack this week has further raised the stakes for the military’s operations in northern Mali.

It is often noted that the importance of reclaiming the country’s north to some of Bamako’s most influential circles is underappreciated by those in the West. However, the manner in which the junta has prioritised military actions in northern Mali has come at a hefty price, with its heavy focus here playing a part in JNIM’s recent successes — including this week’s attack on Bamako.

What Lies Next for Mali Under Goïta’s Junta?

Tough decisions now lie ahead for the political leadership in Bamako. Another major misstep could prove to be a fatal blow for Goïta, placing even more pressure on the success of Malian and Russian forces operations in the country’s north. Yet a potential victory there will do little to solve the more existential threat to the junta, JNIM. Having now expanded and entrenched itself in the Koulikoro Region surrounding Bamako, the al-Qaeda affiliate will be difficult to displace — particularly if the government continues to deploy the same ineffective counterterrorism measures.

The attack on Bamako symbolises Goïta’s failure to adequately combat the violent extremist threat growing inside his country’s borders. Unfortunately for the leader, this attack is probably also a glance into the future. JNIM is likely to continue encroaching on the territory surrounding Bamako, gradually applying pressure on the capital through similar violent incursions, as well as via attacks on major roads leading to the city.

The Malian government has the capacity to better defend the capital, but doing so may come at the cost of protecting other strategically important sites in the country. JNIM’s growing presence in southern Mali not only endangers Bamako and other major cities and towns, but also the country’s gold mines, which are overwhelmingly found in the regions of Sikasso, Koulikoro, and Kayes. The junta must now carefully balance these competing aims, for the loss of a town, city, gold mine, or other important location could be the catalyst for yet another regime change.