JNIM's External Communications in 2025

Understanding JNIM's Contemporary Narratives, Themes, and Strategic Focus.

Established in 2017 as a coalition between several jihadist groups based in the Sahel and North Africa, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa’l-Muslimin (JNIM) has risen to become one of the world’s most powerful terrorist organisations. Consequently, the actions of al-Qaeda’s West Africa branch are now increasingly shaping the future of the Sahel states, as well as a growing number of countries nearby.

As with any jihadist organisation, JNIM remains shrouded by secrecy, causing analysis on the group to be heavily centred around its offensive actions. However, JNIM is not just a perpetrator of violence, it is now also a dominant political, religious, and social force - as is being increasingly demonstrated in its media publications.

This article will explore JNIM’s wide range of media releases so far in 2025, which have primarily focused on its da’wah campaign, training camps, Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr celebrations, and the atrocities committed by the Sahel’s military juntas and their security partners.

While there are limitations to drawing assumptions from a terrorist group’s external communications, they offer a glimpse into its long-term strategy and worldview. JNIM’s publications this year thus provide an opportunity to gain a more holistic understanding of its multidimensional role in the region.

Da’wah Campaign

Jihadist groups use da’wah (proselytising) activities to spread their interpretation of Islam, making them an essential tool for expanding influence and gaining support. Since the beginning of the year, JNIM has released three photosets showcasing its proselytising campaign, all of which, according to the group, were taken in Mali.

Showing JNIM members speaking indoors to dozens of men - all of whom appear to be civilians - two of these publications, taken in the Koulikoro and Mopti regions, are broadly similar in style, setting, and audience. Despite these parallels, evidence of da’wah activities in Koulikoro - which encompasses Bamako - also serves to highlight JNIM’s tightening grip around the Malian capital.

Since early 2023, the al-Qaeda branch has embarked on a campaign to suffocate the capital city via attacks on major roadways and security infrastructure. Critical Threats has assessed that JNIM’s growing support zones in northern Koulikoro play a key role in facilitating its offensive operations.

Indeed, these non-kinetic activities aid JNIM’s expansion into places such as Koulikoro, as they allow members to demonstrate their ability to understand and address local grievances, as well as share religious ideology. By positioning itself as a local actor involved in community level issues and fostering trust along religious lines, the group is able to enhance its ability to violently pressure the state.

JNIM’s third publication - captured in the self-named ‘Aribanda’ region - stands in stark contrast from the two aforementioned. These images depict an outdoor gathering held under the cover of trees, seemingly attended by JNIM members, with many wearing a litham (turban / face veil) and carrying weapons. This meeting was likely held to provide ideological guidance and relay details of military strategy, reiterating the religious dimensions to its armed struggle.

JNIM Camps

Da’wah activities are one of the non-violent tools JNIM deploys to establish and consolidate influence. Once positioned within a community, terrorists can extract a range of resources from the local population, including new members. Since the beginning of the year, JNIM has showcased its active recruitment drive and growing levels of professionalism as a fighting force via four publications of its camps - three of which were captured in Mali and the other in Burkina Faso.

Although sharing similar traits and characteristics, each release provides unique insights into JNIM’s operations. Published in January, the first images were reportedly taken at the ‘Tariq bin Zayed’ camp in the Kidal region. Unlike the two subsequent releases in Mali, militants are shown ceremonially posing, as opposed to undergoing training.

The camp shares a name with one of al-Qaeda’s longest standing and once strongest battalions in the region - Katibat Tariq ibn Ziyad - which merged into JNIM in 2017. While it remains unclear if the fighters are part of this battalion, or another based in Kidal, such as Ansar Dine - one of JNIM’s oldest subgroups, loyal to its Tuareg leader and founder, Iyad Ag Ghali - it is highly likely that those depicted are experienced members.

The other two publicised camps in Mali were reportedly located in the Macina and Sikasso regions, both of which, despite the slight variations in the sophistication of their training, portray JNIM as a well-trained, professional fighting force.

At the camp in Macina, which was not given an official name, fighters are shown undergoing more advanced training, such as hand-to-hand combat and firing drills as small units. All wearing camo trousers, t-shirts, face coverings, as well as military-style boots, those in attendance look more like soldiers than militants. Likewise, images from the ‘Khalid bin Al-Walid’ camp in Sikasso show members in uniform practicing more basic exercises, including drills using makeshift equipment and weapons handling.

While over the years Kidal and Macina have each become synonymous with JNIM activity, the organisation has not historically held a significant foothold in Sikasso. The first-ever piece of evidence of a camp in the region draws attention to JNIM’s growing presence in southern Mali, which has also been demonstrated by its increasing number of attacks.

Trainees reportedly hailed from local Bambara and Malinké communities, who are associated far less with jihadism than the Sahel’s Fulani, Tuareg, and Arab populations. These images are an implicit demonstration that JNIM’s message is resonating with a wide range of backgrounds - even among communities perceived to be less susceptible to the allures of jihadism.

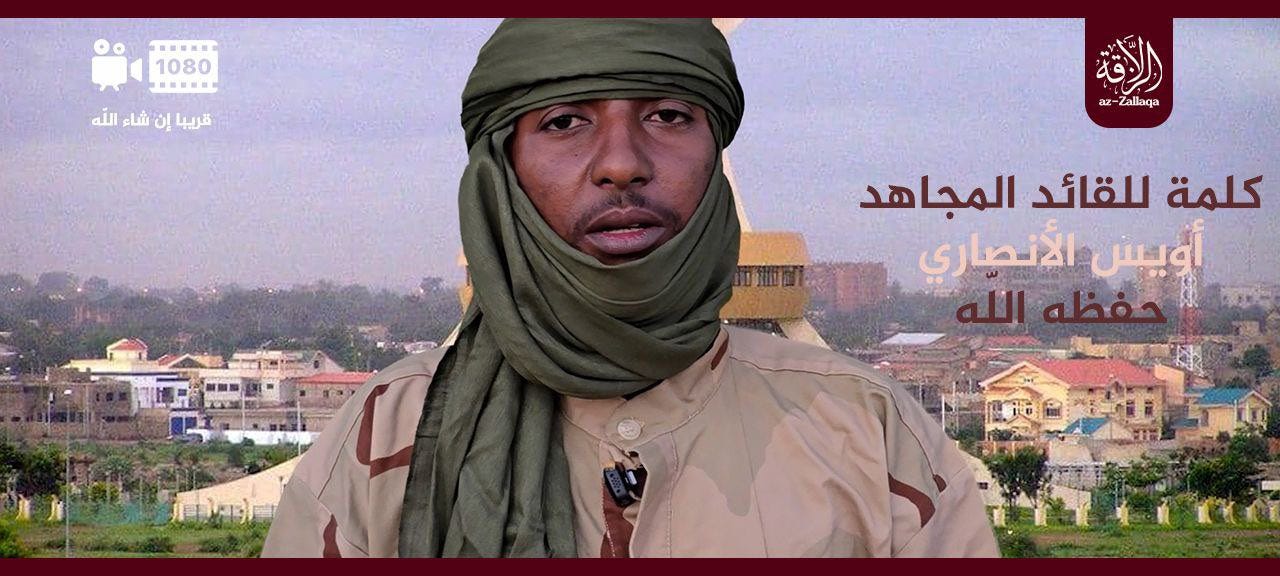

Released in late April, footage taken in the desert of Burkina Faso also underscores JNIM’s attempts to broaden its support base, with members of the group disseminating an important message in three different languages - a unique dimension examined later. As with the images captured at the camp in Kidal, the video showed scores of militants gathered in formation, rather than conducting training drills, seemingly as a show of force to amplify the impact of its message.

Ramadan & Eid al-Fitr Celebrations

Further showcasing the JNIM’s geographical spread and diverse make-up was the extensive amount of coverage provided to its Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr celebrations. In and around the holy month of Ramadan - which began on 28 February and ended on 29 March, followed by the three-day Eid al-Fitr - JNIM released at least ten photosets.

These gatherings were reportedly held in Macina; Burkina Faso; Timbuktu; Aribanda; Gao; and Niger. Images from Kidal, Benin, and Togo were distinctly missing - indicating a strategic emphasis on other regions, a more limited footprint in these locations, or likely a combination of both.

Exemplifying the levels of religious devotion throughout its ranks, JNIM’s Ramadan and Eid publications showed members praying, reading and reciting the Quran, as well as partaking in Iftar (breaking their fast). Iftar meals were typically composed of a diverse and well-presented range of fresh fruit, meat, and vegetables - demonstrating that members are well-treated and able to access a variety of resources.

Regional variations among JNIM’s subgroups were identifiable in militant attire and headwear, alongside flags and rugs pictured in the background. Each publication from this religious period broadly reflected the levels of presence, control, and confidence each branch enjoys in their respective areas of operation, with celebrations ranging from small, sheltered events attended by tens of fighters to large gatherings held in the open.

For instance, in the sole release from Niger - where one of the JNIM’s newest branches, Katiba Hanifa, is located - there appear to be no more than 30 fighters gathered near the cover of a tree line. By contrast, there are photos captured of fighters from the Aribanda battalion, which holds a far more consolidated position in its zone of influence, showing at least 100 militants assembled out in the open.

Notably pictured at the large Eid al-Fitr gathering in Aribanda were dozens of veiled women and children, seemingly displayed to portray JNIM as not only a militant group, but also a community where families are welcome. The inclusion of women and children also highlights the longevity of the jihadist organisation’s project, as well as its efforts to cultivate a future generation of fighters.

Eid Leadership Meeting

The size of some of JNIM’s Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr celebrations were yet another reminder of its meteoric rise to the position of dominance it holds today. They also exemplified the levels of freedom many of its members have to operate across swathes of the region - an observation reinforced by evidence of an Eid al-Fitr meeting between JNIM’s top leadership and high-ranking commanders.

Meetings involving the organisation’s most senior leaders and commanders from across the region are a rare occurrence, at least publicly. This significant gathering not only took place in broad daylight, but was also reportedly held approximately 300 km from Bamako. As with its Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr publications, evidence of this meeting drew attention to the Sahelian militaries' inability to sufficiently monitor and disrupt JNIM’s operations.

Helping dispel rumours of internal friction, some JNIM’s most senior leaders - including Iyad Ag Ghali, Sidan Ag-Hitta, Abd al-Rahman Talha al-Libi, Amadou Koufa, and Mahmoud Barry - were in attendance. As attacks mount across the region, this meeting will have seen important talks take place on how JNIM can embark on a new era of political influence and territorial control. Alghabass Ag Intalla, a prominent Tuareg leader, was also present at the meeting.

Although not a JNIM member, Ag Intalla was reportedly in attendance as a mediator between the al-Qaeda branch and the Azawad Liberation Front (FLA), a Tuareg separatist rebel group. In early March, reports surfaced indicating that JNIM and the rebels are exploring ways to strengthen their relationship to advance toward their primary political aims in Mali. Ag Intalla’s attendance at this gathering was a further demonstration of this deepening partnership, as well as the intertwined nature of JNIM’s religious, political, and military aims.

Speeches and Written Statements

Mahmoud Barry - Katiba Macina’s second-in-command and one of JNIM’s primary spokesmen - was filmed giving a speech at this rare event. Barry’s speech reflected the dramatic transformation the Sahelian security landscape has undergone in recent years, driven by the ruling junta's pivot away from Western security partners - who had been actively engaged in counterterrorism operations between 2012-2023 - toward countries such as Russia and Turkey.

Consequently, Russia, which has deployed personnel to fight on the frontlines in Mali, as well as to provide training and other security assistance in Burkina Faso and Niger, and Turkey, whose drones have helped fill the void left by Western airpower, have seen their increasingly important role in the region come under significant scrutiny in JNIM’s recent external publications.

In his speech, Barry condemned ongoing civilian massacres by state security personnel and Russian troops, alongside the mounting collateral damage caused by strikes from Turkish-made drones. He also decried the ongoing atrocities committed by Burkina Faso’s Volunteers for Defence of the Homeland (VDP), a civilian auxiliary force that has become a central feature of Captain Ibrahim Troaré’s strategy to combat jihadist groups.

In 2024 alone, 2,430 civilian deaths were attributed to Sahelian security forces and their Russian partners - more than the amount of civilians killed by extremists. JNIM has been leveraging these inverted conflict dynamics in its external communications throughout 2025 to portray itself as a protector of the region’s civilian population and broaden its support base, with the involvement of foreign troops and weaponry adding to the potency of its messaging.

Following the infamous atrocities committed by members Burkina Faso’s security apparatus against Fulani communities around Sourou region’s Solenzo, Ousmane Dicko - brother of Jaafar Dicko, leader of the Ansarul Islam subgroup - gave a several minute-long speech condemning these acts of brutality. He also pledged to get revenge for the persistent killings of civilians, regardless of their identity, and called for all ethnicities to join JNIM.

As it had warned, JNIM has gone on to conduct a campaign of violence that has left hundreds of dead in its wake. Among the most notable of these retributive attacks in Burkina Faso came against a military base in Diapaga and the besieged city of Djibo - which combined likely killed over 200 people - as well against villages that had recently been recaptured by Burkinabè security forces in Sourou, whereby around 100 men and boys were slaughtered for allegedly seeking to join the VDP.

In a public release on 8 April, Jafar Dicko - referred to as Abu Mahmood al-Ansari - stated the attack in Diapaga was only "the beginning of revenge for Solenzo,” and thanked Human Rights Watch and international media outlets for their coverage of the atrocities. Ousamne Dicko also claimed JNIM’s devastating attack on Djibo was revenge for these ongoing atrocities in Burkina Faso in a video recording released on 13 May.

After making numerous calls earlier in the year for increased condemnation of civilian killings from the global community, Jafar Dicko’s expression of gratitude to the international organisations in April was a calculated decision to legitimise JNIM’s mounting violence in Burkina Faso and to incite deeper international criticism of the Sahel’s military governments.

These attempts to erode the legitimacy of Sahel’s juntas are likely part of a strategy that may eventually allow JNIM to achieve some of its aims through internationally recognised negotiations - or potentially even proclaim itself a rightful ruler and administrator of territory - and avoid the mistakes of 2012 which prompted a French-led military intervention.

JNIM still has considerable amounts of work to do before it can try and achieve such a momentous undertaking, among which includes reducing the armed forces support of the juntas, alongside the civilian population. In the footage captured in the desert of Burkina Faso examined earlier, JNIM released a message to the people of Burkina Faso in three languages, claiming that its war is not against the civilian population, but against the military and the VDP. Any person wishing to leave these forces would be able to return home and live in peace, it also claimed.

This direct message marks a distinct shift in JNIM’s communication strategy, with it ostensibly attempting to capitalise on faltering morale within Burkina’s armed forces - caused largely by its ongoing brutal campaign of violence, no less - and further erode the loyalty of rank-and-file soldiers to their leader, Captain Ibrahim Traoré.

By reaffirming to Burkina Faso’s civilian population that they will not be subject to violence, so long as they do not side with the military and the VDP, and offering soldiers a potential escape route during a period of particularly intense bloodshed, JNIM is using its external messaging to increase the likelihood of its violence translating into tangible social, religious, and political outcomes.

Key Takeaways

The publications JNIM has released so far this year have offered important perspectives into its violent and non-violent activity. Further displays of the organisation’s da’wah campaign have highlighted its non-kinetic efforts to penetrate the social, political, and religious fabric of communities across the region and enable its violent activity.

Moreover, publications of JNIM’s camps have evidenced its ability to establish itself in new territory and recruit from a broader range of ethnic groups such as the Bambara and Malinké - further underscoring its broadening appeal. The images also draw attention to JNIM’s growing levels of professionalism as a combat force as it continues to escalate its violence.

The extensive amount of media coverage JNIM provided to its Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr celebrations showcased its religious devotion, its vast territorial reach, its diversity, and the relative levels of freedom its fighters and high-ranking leaders alike have to operate across the Sahel. The scale of some of these events also support JNIM’s recruitment drive, with the rare inclusion of women and children in a select number of images allowing it to project inclusivity and longevity.

Furthermore, written statements and speeches released by JNIM over the past several months have focused on several major themes - namely the killing of civilians by state forces, Russian troops, and Turkish-made drones. JNIM is exploiting these persistent atrocities to justify its violence and portray itself as a legitimate protector of the people - regardless of their background.

JNIM’s references to the global community are illustrative of its growing perception that it may now be able gain international legitimacy at the expense of regional governments. These direct references have likely been made to improve its chances of transitioning from terrorist group to recognised governing authority.

JNIM’s external communications have showcased its ongoing efforts to lay the groundwork to achieve its lofty and intertwined aspirations of political, religious, and military dominance in the Sahel and beyond. However, focusing overwhelmingly on activity in Mali and Burkina Faso, which are currently at the forefront of its violence actions - reportedly due to their repression of the Fulani community, according to an unofficial voice recording from Ousmane Dicko - JNIM’s external communications reiterate that despite its ongoing expansion into nearby states, it is these two states that remain firmly at the centre of its ambitions.

Thank you Sir for this insightful article regarding the Sahel Situation.

As a sahelien I know that this situation is very complex and the way forward could be by negotiations.

The rebels should not be excluded without thorough assessment of their needs and efforts to address them.